Building a Bridge to Social Security

If you read any early retirement blogs, you may have encountered a rule of thumb that says something like “you need to save 25 times your annual expenses in order to retire”. That 25 number, the expense multiplier, comes from a 4% withdrawal assumption. So if you withdraw 4% from your portfolio to cover your expenses, that means your portfolio must be at least as big as the inverse of 4% or 25. Because you only retire once, I prefer to be a little more conservative and use an expense multiplier of 30 which corresponds to a 3.33% withdrawal rate.

While this kind of rule is a great rule of thumb for giving people an idea of how much money they will need to save, it tends to ignore the income that you will earn from a future income stream such as social security or a pension1. In the early retirement circles the effects of social security tend to be ignored perhaps because it seems like far-off and insignificant event. But the effects of that extra income increase over time so your financial independence could be closer than you previously thought.

Simple Example

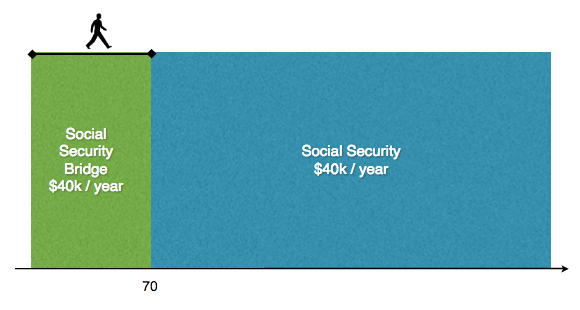

To illustrate the effects with an extreme example, consider the case of somebody named Woodrow who is 69 years old and has expenses of $40,000/year. Furthermore, if Woodrow expects to receive $40,000/year from social security at age 702, then he will only need to have savings of $40,000 to be able to retire right now. In this extreme example, Woodrow’s expense multiplier is 1 because he only needs to have saved 1 times his annual expenses in order to retire now. Think of needed savings as a 1-year bridge that allow Woodrow to live comfortably until his full social security benefits kick in.

In the illustration above, the green area represents the funds that are needed to fill the gap until social security kicks in.

In scenarios like this, where your future social security payments will cover your expenses,

it’s fairly easy to extrapolate this simple example to longer time periods.

In such scenarios you only need to save enough money to get to the age when

you will begin collecting social security.

So if Woodrow had been age 60 in the above example, he would need to have savings

of 10*$50,000 or $500,000 in order to cover his expenses for the 10 years before

he received social security. His expense multiplier is the number of

years until he begins collecting social security.

Also of note, if Woodrow is 30 or more years from receiving social security, he doesn’t necessarily need a portfolio bigger than 30 times his expenses because, theoretically he should be able to live off of the 3.33% withdrawal indefinitely (or whatever you consider to be a safe withdrawal rate).

Early Retirement Example

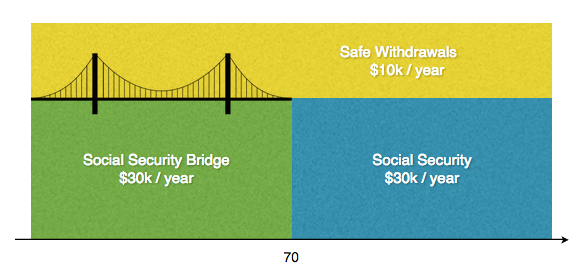

The above example is interesting and illustrates how accounting for social security can dramatically reduce a person’s expense multiplier. But early retirees are more likely to be in a situation where the social security amount will not cover all of their expenses in the future because they may not have contributed a full 35 years into the system. In this case, a social security bridge may need to be supplemented by additional withdrawals to meet spending needs.

Let’s consider another person named Priscilla who is aged 55 and estimates that

she will receive $30k/year (in today’s dollars) from social security if she waits

until age 70.

But Priscilla’s expenses are $40k/year. To bridge the 15-year social security gap,

Priscilla needs 15 times the $30k, or $450k to get her to the level of income

that social security will provide.

Then she will need an additional piece of her portfolio to get her the

extra $10k/year needed to cover her expenses. Using a 3.33% withdrawal rate

means Priscilla will need an additional 30*$10k or $300k.

In Priscilla’s example she would need $750k to retire at age 55 with $40k in

expenses. This means that her expense multiplier is reduced from 30

(inverse of 3.33%) to 750k/40k or 18.75.

To put it another way, without considering social security Priscilla might have

concluded that she needed to save 30*40k or $1.2m, which is 60% more than the $750k

she actually needs when taking social security into account.

Very Early Retirement Example

Retiring very early can put you into a situation where building a social

security bridge doesn’t make sense initially. For example, if you retire at age 30, then

building a bridge for 40 years means you might start withdrawing funds at a 2.5%

rate which is likely more conservative than necessary.

To get around this problem, you can initially take withdrawals at your preferred

safe withdrawal rate until you hit the age of 70-1/withdrawal_rate.

Then you can implement a social security bridge from that age forward.

This is illustrated below where initially all income is from safe withdrawals,

then a social security bridge kicks in later.

Consider the case of Gunther who is retiring at age 35. Good for you Gunther! Because Gunther has contributed into social security for much less time than the maximum of 35 years3, his estimated social security payments at age 70 will only be $10k. Because his social security payments are so far in the future, he needs to have an initial portfolio equal to his expenses divided by his withdrawal rate.

So if Gunther needs $40k of income and wants to use a 3.33% withdrawal rate,

he should start with a portfolio of 30*$40k or $1.2m. Then, at age 40, he

can break his portfolio into two pieces. One piece, $300k (or higher depending

on inflation and social security adjustments), will be used as

a social security bridge. The remaining part of his portfolio can continue

at the safe withdrawal rate.

Why would Gunther do use a social security brige at all? The funds in the social security bridge piece of his portfolio will be withdrawn at ever increasing withdrawal rate until age 70. This means that Gunther’s overall withdrawal rate that is effectively higher than 3.33% and increases as he approaches age 70 when social security will takes over. In other words, he can safely increase his income between ages 40 and 70 beyond what he would have received if he had maintained a 3.33% withdrawal rate.

One thing that very early retirees should be aware of is that you need to contribute into the social security system at least 40 quarters (10 years) in order to be eligible for social security payments. So if you’re an extreme saver and can retire in 9 years and 11 months, it would probably be a good idea to work that extra month to become eligible for social security benefits later in life. If you’re lucky enough to be in this situation, check the social security site to make sure you don’t leave yourself short.

The Bridge Fund

How do you build a social security bridge? The trick is to allocate a chunk of money that will pay you an income equal to what you expect to receive from social security in the future. Fortunately, the social security administration reports your expected benefits in today’s dollars and adjusts them up every year based on current inflation. This makes it easier to project how much money you need now because the calculations are done in current dollars.

There are several ways you could build a bridge fund.

-

Bond ladder - you could build a bond ladder for the bridge period. This might work well for somebody between 65 and 70 who wants to delay taking social security for a few years. But if you are more than 5 years from taking social security, you might want to take a little more risk so that you can keep up with inflation.

-

Single Premium Immediate Annuities - an insurance company would be happy to sell you a SPIA that is “term certain”. For example, if you are 60, you could buy a 10-year term-certain immediate annuity that pays you a fixed income for the next 10 years. You could also buy one with inflation protection but that will cost a little more. While I think lifetime annuities are a really good option to protect against longevity risk (outliving your money), a term-certain annuity doesn’t have an actuarial component associated with it so you might be able to do better elsewhere. But there’s something to be said for a guaranteed stream of income so perhaps this option will appeal to you.

-

Income Replacement Funds - Fidelity offers a particular type of fund called Income Replacement Funds that are designed to distribute your invested funds over a particular period of time. One of the stated purposes of these funds is as a bridge to a future income stream such as a pension or social security. The funds do this by investing in a mix of stocks, bonds, and cash equivalents and become more conservative as the they nears their end date. Think of this as a period-certain annuity with more risk and possibly more return. This might be a good choice if you can handle a little more risk and like something simple.

-

DIY Bridge Fund - You could build your own bridge fund using low-cost index funds. In a future article I will propose a way to build your own bridge fund using a simple allocation of low-cost funds.

Math

Now is the time for the geeky part of the article. Let’s try to develop an equation to describe the effective expense multiplier that takes future social security income into account.

The equation for your future income can be written as,

income_total = income_ss + porfolio_remaining*withdrawal_rate

If you consider that your future portfolio will be reduced by the amount of income that was used as a social security bridge, then the amount of income you have left to apply your withdrawal rate to is approximately,

porfolio_remaining = portfolio_current - years_until_ss * income_ss

The 2nd term of the above equation represents an approximation of how much your portfolio will be reduced by building your social security bridge. This will vary depending on how you build that bridge but this is a good ballpark estimate.

Ultimately we’re interested in determining the expense multiplier needed for retirement. In other words, how big would my portfolio need to be in order to be retire today. Defining the effective expense multiplier as,

multiplier_effective = portfolio_current / income_total

Further, let’s define the safe withdrawal rate multiplier as just

multiplier_safe = 1 / withdrawal_safe

Plugging all those equations in and solving for multiplier_effective

gives:

multiplier_effective = multiplier_safe - (income_ss/income_total) * (multiplier_safe - years_until_ss)

Notice that the closer you are to collecting social security, the smaller your effective expense multiplier is. So each year you do this calculation will bring you closer to retirement even if your portfolio doesn’t grow. The amount you will reduce your effective expense multiplier each year is the ratio of your social security income to your total needed income.

Let’s try applying this equation to Woodrow’s example where he will retire in 1 years:

multiplier_effective = 30 - (50k/50k) * (30 - 1) = 30 - 29 = 1

Which is exactly as we expect. In fact, in cases like Woodrow’s, where the income from social security equals (or exceeds) the total income needed, then the equation for the effective expense multiplier reduces to:

multiplier_effective = multiplier_safe - 1 * (multiplier_safe - years_until_ss)

= years_until_ss

Now try Priscilla’s example,

multiplier_effective = 30 - (30k/40k)*(30-15) = 30 - 11.25 = 18.75

Priscilla’s effective withdrawal rate in the first year would be approximately

1/18.75 or 5.33%. You may be thinking that a withdrawal of 5.33% is too high

but remember, she is still withdrawing a conservative 3.33% on the funds outside

of the bridge fund.

Also, if Priscilla waits one more year to retire, then her effective expense multiplier would go down by (30k/40k) or 0.75, so if she waits until age 56 her expense multiplier would be 18.0 so she could be closer to retirement even if her portfolio didn’t grow at all.

Some people would have you believe that social security will be greatly diminished in the future. Whether or not that’s true, time will tell. If you are worried about this possibility then simply adjust downward your social security estimate in the above equations to a level you feel comfortable with4.

Summary

The inverse of the withdrawal rate is often used as an expense multiplier to figure out how big a person’s portfolio needs to be to cover retirement expenses. Oftentimes this is stated in terms of how big a portfolio needs to be in order to cover expenses above social security income. It’s common for early retirees to assume that this expense multiplier also applies to their total income but it doesn’t account for future income streams like social security.

By considering how much your future social security income will affect your expense multiplier, you may find that you can retire earlier than you previously thought. And every year you wait, your expense multiplier goes down so you can move closer to achieving retirement even when your portfolio stagnates.

Related

-

Most of this article refers to social security for brevity’s sake but the same principles apply equally to other future income streams such as pensions. ↩

-

For most people, delaying social security benefits to age 70 is the best decision, so all examples in this article assume that social security benefits will start at that age. ↩

-

The Social Security Administration uses the maximum 35 years of earnings over your entire working career in their formula to determine your benefits. ↩

-

Yes, I ended that sentence with a preposition. And I also think that social security will be available when I’m eligible for it. That’s how crazy I am. ↩