The 30-30 Withdrawal Strategy

Withdrawing funds from your portfolio can be tricky. On the one hand, you want to make sure you take enough income to support your expenses. On the other hand, you want make sure you don’t run out of money by taking too much. Most withdrawal strategies break down as either a constant dollar or constant percentage or a hybrid of the two.

Constant-dollar withdrawal strategies tend to start with some amount, like 4%, and take that dollar amount each year. Optionally, the amount could be increased to account for inflation each year. While these constant dollar strategies are a great tool for academia to study the effects of different rates, they have the possibility of failure (running out of money) if you continue to withdraw the same amount of money without regard for what your portfolio is doing.

Constant-percentage withdrawal strategies get rid of the possibility of failure by just taking a fixed percentage out of the portfolio every year, regardless of what the market does. This is an improvement over constant dollar strategies because you can’t run out of money, but it does mean that your income will be subject to the vagaries of the market. If you can stomach those swings or have other sources of income to buffer those swings, then this strategy might work fine for you.

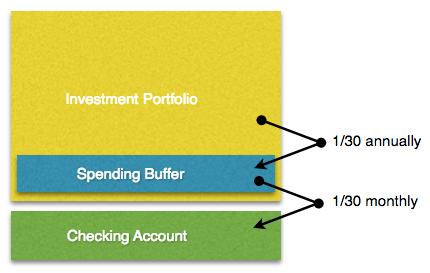

The “30-30 Withdrawal Strategy” described by this article has the advantages of a constant-percentage strategy but attempts to buffer the market variations by using shock-absorbing buffer. The name of the strategy comes from the withdrawal rate and buffer size. The basic idea of this strategy is that you move a fixed percentage of your portfolio (1/30) into a spending buffer each year, then you take a fixed amount from that buffer (1/30) for monthly living expenses.

Withdrawal Rate of 1/30

The “30-30 Withdrawal Strategy” uses a withdrawal rate of 3.33% for a couple of reasons. First, it’s easy to remember. Second and more importantly, it’s in the realm of withdrawal rates that should, over time, allow you to keep up with inflation.

Where does the 3.33% come from? Recall from the Safe Withdrawal Rates for Vampires article that the safe withdrawal rate for someone who needs their money to last forever is given by the following equation.

withdrawal_rate <= (appreciation - inflation) / (1 + appreciation)

It is not possible to know what future portfolio appreciation will be, but historically a 50/50 stock/bond portfolio would have returned around 7-8%. But when it comes to retirement, I prefer to be a little more conservative. So let’s chop about 2% off of 7.5% to get a conservative future appreciation estimate of 5.5%.

Inflation is also a little tricky. Currently inflation is running close to zero but the Fed has said that they are aiming to keep it close to 2%. So, for the sake of this calculation, let’s assume the Fed is able to keep inflation near 2%.

Plugging those numbers into the above equation, we get

withdrawal_rate <= (0.055 - 0.02) / (1 + 0.055) = 3.32%

This withdrawal rate is also very close to 1/30 which means that you can just divide your entire portfolio value by 30 to arrive at the amount needed for an annual withdrawal.

You may disagree with the assumptions or have a different type of investment portfolio with different return assumptions. But understanding how I arrived at the number may allow you to choose your own number for the withdrawal rate.

30-month Buffer

Buffering the annual withdrawals will help to smooth out the bumps in the portfolio returns. The idea of the buffer is that, each year, you take your annual withdrawal and immediately put that into your income buffer. Then you divide that income buffer by the size of the buffer in months to arrive at your income level for the next year.

Using a 30-month buffer is frankly, somewhat arbitrary. I chose 30 months (2.5 years) partly because it has the number 30 in it, but also because I personally want to keep the buffer relatively small so that I can keep as much of my portfolio invested as possible. As with the withdrawal rate, you can use a buffer size of your choosing. The bigger the buffer is, the smoother your income variations will be, but a bigger buffer also means that less of your money is invested.

Step-by-Step

Let’s go through an example portfolio to see how this works. First, let’s start with a portfolio of $900,000 (it divides by 30 nicely).

-

Create your initial spending buffer by dividing your portfolio by 30 then multiplying by 2.5. This represents 2.5 years worth of future spending so put it in a safe place like an interest-bearing account, short-term bonds, money-market, or similar. For the example $900,000 portfolio, $900,000/30 = $30,000 so you would put $75,000 into your initial buffer.

-

Divide your buffer balance by 30 to get your monthly income level and set up an automatic withdrawal of that amount that goes into your spending/checking account. In our example, $75,000/30 = $2500/month.

-

Live off of the income for 12 months. After 12 months your buffer should have approximately $45,000 left in it.

-

At the end of each year, recompute your portfolio value and move 1/30 of it into your buffer. In our example, let’s assume that the invested portion of $825,000 increased to $885,000. Add that to the remaining buffer ($45,000) to get your new portfolio value of $930,000. Divide that by 30 and move that amount into your spending buffer. $930,000/30 = $31,000. Your spending buffer should now have $76,000.

-

Go back to Step 2 and repeat annually.

One thing to note is that I am including the buffer as part of the overall portfolio value when doing the above calculations. If you prefer to keep it separate from the investment portfolio, then you could use a divisor of 27.5 (instead of 30) on just the investment portfolio to achieve similar results.

Astute readers might notice that, even though the investment portfolio increased by (885/825) 7.3%, the income in the next year will only rise by (76000/75000) 1.33% which is below our assumed inflation rate of 2%. This is because the initial buffer was created without taking inflation into account. Over time this effect should go away and the average increases will keep pace with inflation. If you want to take that into account from the get-go, you could create a smaller initial buffer (e.g. 2.4x) which means you would receive less income initially. But, I personally prefer to start with a slightly larger income and suffer the smaller initial income adjustment until the buffering “catches up”.

Variation: Different Withdrawal Rates

The withdrawal rate of 3.33% was chosen with a fair amount of hand-waving but represents what I would consider to be a fairly safe rate that has a reasonable chance of keeping up with inflation. However, if you’re a risk taker and/or have other streams of income to buffer your income, then higher rates aren’t unreasonable. For example, if you are comfortable with a 4% withdrawal, then you could use 25 as your divisor instead of 30.

Alternatively, maybe you could start with 30 then decrease it until you settle in on a number that seems to suit you.

Variation: Different Buffer Sizes

While 2.5 years is a handy size for the “30-30 Strategy”, it’s certainly not written in stone. For example a 6-year strategy might play well into a Roth ladder if so you might choose to create a buffer of 72 months. Bigger buffers also have the advantage of smoothing out the investment returns even more and giving you a more predictable income stream. But the downside of larger buffers is removing money from your investment pool so you might want to consider investing part of a larger buffer into a medium-term bond fund or something similar.

Summary

The “30-30 Withdrawal Strategy” is an easy mechanism for taking income from a portfolio. Divide your portfolio by 30 to figure out much to put into your spending buffer. Then divide the spending buffer by 30 to figure out how much to withdraw as income every month. Rinse and repeat.